When we think of heritage, it is very unlikely that we would think of jellyfish, but guess what? Just like the leopard, the protea and the African penguin forms part of South Africa’s natural heritage, so do our endemic and unique jellyfish.

So much so, that the country has something called SA Jelly Lab where researchers and scientists spend their time investigating, researching and recording the jellyfish of South Africa.

The University of the Western Cape (UWC) has been conducting jellyfish research for over 15 years. The SA Jelly Lab consists of a group of scientists from the university who specialise in all things jellyfish, have expertise in a range of fields and who conducts research across the oceans of the world.

One of the many projects this group is involved with is investigating the occurrences of jellyfish blooms within several estuaries along the south and east coast of South Africa.

There have been sightings of jellyfish within estuaries stretching from the Breede River all the way to Kosi Bay. The presence of a few new species of jellyfish, belonging to the genus Crambione, is currently under investigation. These jellyfish inhabit the waters far up the estuaries where the salinity is low. So far, Crambione has been collected in the Breede -, Keurbooms -, Kromme -, Mgwalana – and Kwellera Rivers, but could possibly occur in even more.

It was originally thought that the jellies within these estuaries belonged to one species and consisted of different populations but genetic results suggest that each is a new species. At the moment, SA Jelly Lab is paying special attention to describing each species, looking into their distributions, as well as the variations between the different species – from a morphological to a genetic level.

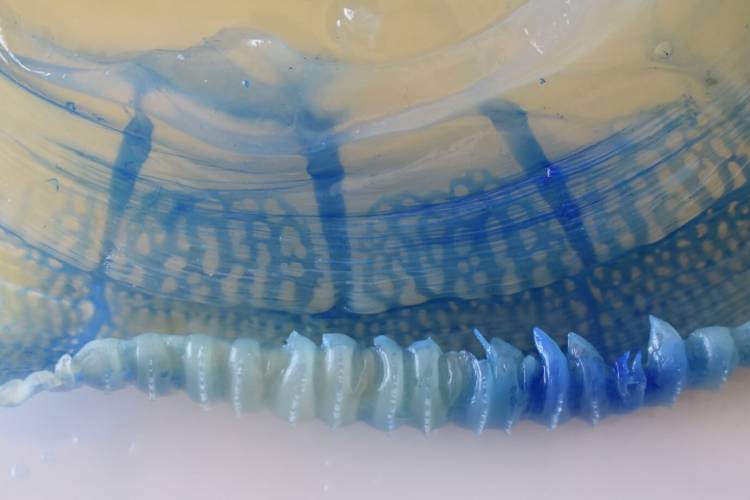

Crambione is a barrel-shaped jellyfish that is mostly reddish-brown in colour. That said, its colour may vary depending on its environment. These jellies lack tentacles but have large “frilly” oral arms used for feeding and deterring predators. Jellies of this genus are edible.

Estuaries differ in their biochemical properties as well as the types of zooplankton (on which jellies mostly feed) found in them. This, in turn, promotes the occurrence of different jelly species, or enable species to evolve and adapt to that specific environment. It is understood that the Crambione species are secluded within their respective estuaries. They do not inhabit the adjacent bays and aren’t able to migrate between estuaries.

In the past, these jellies must have entered each estuary and adapted to survive in that specific environment, with being cut off from the other populations resulting in specification.

An interesting survival strategy of these organisms is its ability to develop specific types of stinging cells, which allows them to adapt to the food web of the environment. They use their stinging cells for feeding as well as deterring predators. Each population of a jellyfish’s stinging cell complement is unique, and research suggests that the different species amongst the different estuaries can be distinguished by using their stinging cell complement alone.

This is almost like a species-specific fingerprint.